In conversation with Jahnavi Phalkey

Netra Prakash

April 19, 2024

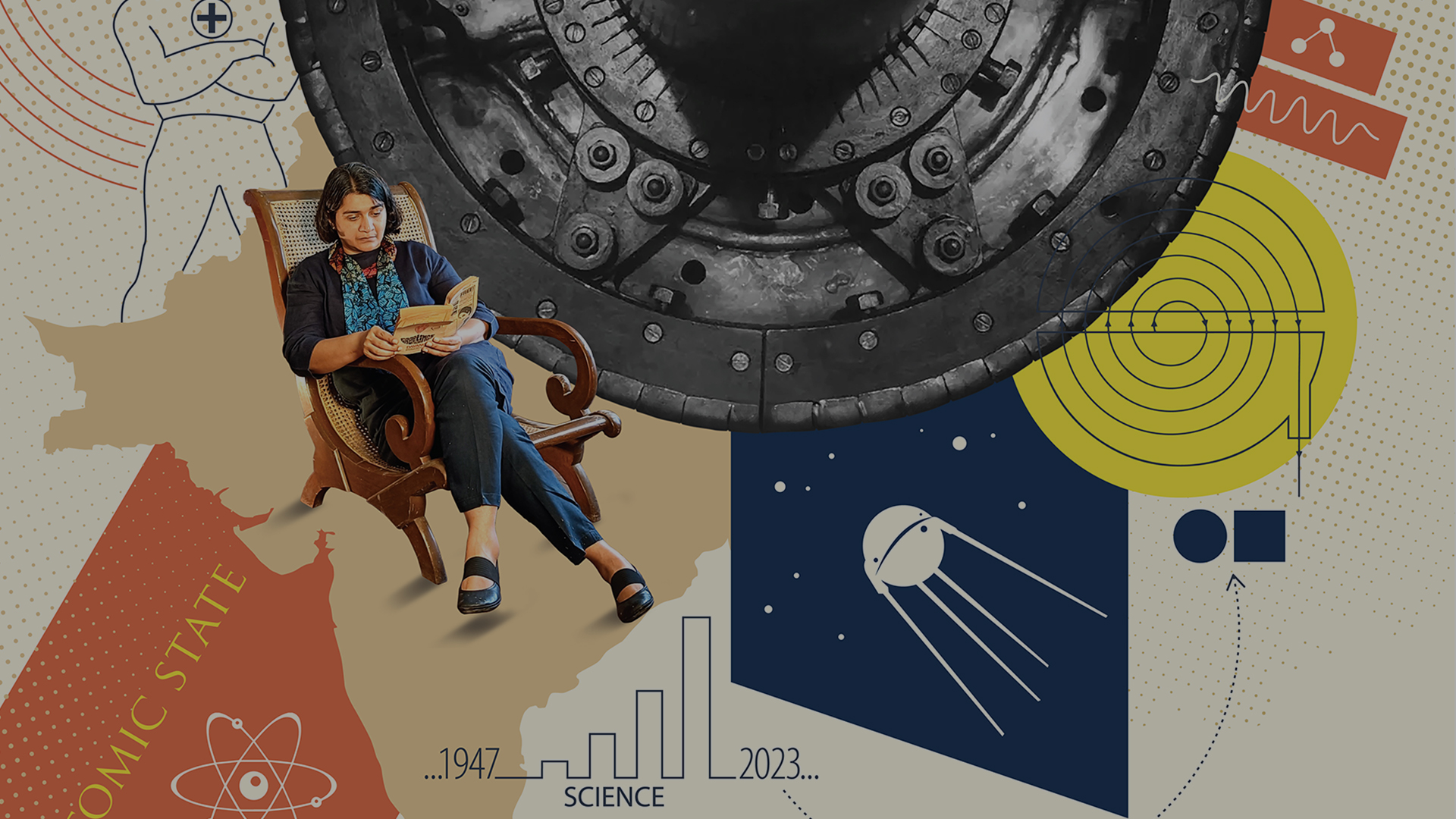

Dr. Jahnavi Phalkey is one of our Foundation’s most versatile laureates. From authoring a book on the origins of Indian nuclear science, to directing a film about the world’s oldest functioning particle accelerator, to becoming founding director of a Gallery which brings science to the Indian public, this science historian has done it all.

Today, Dr. Phalkey shares her journey with high schoolers, and offers us valuable advice as we embark on our own.

1. You’re known for your documentation of the history of science, which is quite an esoteric field, especially in India. What does work as a science historian entail? And how do you get into this field?

For the last six years, I’ve been working in public engagement, but before that, I was a historian of science.

My day as a science historian looked like any other academic’s. Teaching, mentoring, and research took up most of my time. I spent hours going through archives, speaking to people, and reading secondary literature, finally putting it all together to make sense in relation to existing scholarship.

You could get into this field from almost any background. The year that I entered Georgia Tech for my PhD in the history of science and technology, there were six of us: one computer engineer, one mechanical engineer, one electrical engineer, one biologist, one economist, and me, who had studied civics and politics. As you can see, we were from very diverse backgrounds.

2. Does your background influence your work as a science historian?

Yes. Your undergraduate training does, to a significant extent, determine the kinds of questions you can answer.

For example, if you want to understand the changing research questions in the transition from classical physics to quantum physics, someone who is trained in physics is much better suited than I am to answer that. Whereas, if you want to know about the institutional context, organization, where the scientists were coming from, why certain questions were more attractive to them than others: those are the kind of questions that someone with my training can answer.

This doesn’t mean you can’t retrain yourself! When writing The Atomic State, I spent a lot of time trying to understand nuclear physics as a discipline, especially the beginnings of experimental nuclear physics. Though I had no prior training in the field, I audited undergraduate physics classes, attended conferences, and visited lots of facilities. This ensured that the people I spoke to during my research trusted my ability to understand their work. If they didn’t, they probably wouldn’t have answered my questions well or taken my research seriously.

3. You’ve accomplished so much in so many diverse fields: writing The Atomic State, directing films, and founding the Science Gallery Bangalore. Where did the inspiration for each of these different ventures come from?

Different things propel different people. For me, it is usually anger and dissatisfaction.

When I was studying the 20th century history of science, we only learnt about European and American, and to some extent Soviet, science. It was as if India didn’t exist! I knew that couldn’t be true, and I needed to find out what was happening in India, which is how I began my work on The Atomic State.

I made the film Cyclotron, about the world’s oldest functioning particle accelerator, because I was somewhat bored of writing academic papers that would reach only a few people. Many of my cool friends at the time were filmmakers, and I was always fascinated by their work. Also, the story was intriguing because of the people involved. I don’t think I could’ve written a novel to recreate their minds, their attitudes, and their motivations. So, I decided to make a film instead.

The film on agronomy, meanwhile, got made while setting up the Science Gallery. Founding a new institution was an entirely new experience, and I needed to do something I was familiar with. Honestly, making The Gold of a Yellow Plant briefly helped me keep my sanity.

4. A central idea of The Atomic State is that “science does not happen in isolation.” Could you explain how science interacts with politics and society, and what this requires of aspiring scientists?

Science doesn’t just interact with society: it is very much a part of society. Scientists are social creatures, because human beings are social creatures, so science isn’t separate from society.

Let me give you an example from The Atomic State: in the 1930s and 40s, there were three labs trying to establish nuclear physics in India, against the backdrop of the Second World War. In 1938, we found out about nuclear fission. 1945 saw the first use of a nuclear weapon. And in 1947, India became independent.

So, by the end of the Second World War, the nature of nuclear physics had changed: it was no longer about doing physics in the lab, but about how nuclear physics could be used, for defense and for energy. Political leadership at the time realized that for India to remain independent, she had to appear capable of defending herself. As the newest weapon was the atomic bomb, some felt that India needed to have the capacity to develop one. Consequently, the three labs working on nuclear physics became potential candidates for State support. These labs now had to compete not only for resources given that research had become expensive, but also for political attention. Their ability to research nuclear physics was determined by the willingness of the State to fund them, which in turn was determined by the fact that nuclear physics was now tied to the ability to make a weapon.

Nuclear physics might seem like a particularly politically sensitive area, but you’ll find similar scenarios in plenty of other fields. Especially in a country like India, where most research is funded by the State, national priority often shapes what can happen in the lab.

5. We’ve discussed science’s place in the State, but since we’re in the Science Gallery Bangalore, what about the interplay of science and art? How do the two fields complement each other in this extraordinary place?

The model we were supposed to have at the Science Gallery, which came from Dublin, was to bring artists and scholars together to create public engagement. The idea was that if art mediates research, research becomes more accessible.

But in Bangalore, we have revised this model. If Indians in their everyday life are distant from science research, then they’re equally distant from art. Walking into an art gallery is just as alien to us as entering an IISC campus. What we’ve created instead is a space where neither art nor science is prioritized, but rather, questions that matter to everyday life are brought into prominence. We’re agnostic to what form this engagement takes: we have arcade games, card games, things to see, and things to touch.

6. How does the Gallery’s work differ from science communication?

Science communication is when some people know certain information, while some others likely don’t, and so you find a language to communicate this information. It’s a one-way flow, while what we are building in the Gallery is a two-way bridge.

Everyone who comes into the Gallery need not become a climate change expert. The goal is not to understand every scientific concept, but rather how these concepts impact us. What I like to say is that this place doesn’t share with you science, but rather what is around science, to help everyone answer this quesiton: why is science and engineering research central to organising society as well as our life today?

7. How can high schoolers in particular make the most of this place?

I think my key message for high schoolers is to visit us and spend a lot of time here.

In high school, you’re about to make some important life choices. The Indian education system especially is fairly brutal. Once you choose a career, especially a non-science career, there’s no return door. I would recommend that you explore the different avenues that are finally open to Indian youth today, despite the system. Spend time in the gallery. Come for lectures, masterclasses, and workshops: they’re free for everybody, and available in English and Kannada.

Our education system tends to close doors to careers. And what I want the Gallery to do is open these doors. I’d like for young people to hang out here, discover what motivates them, and find their own voices.

8. You’ve taken such a unique career path, and clearly been very successful on it. What advice would you give to high schoolers as we begin to chart our own paths?

In India, we learn to appreciate other people's successes. And we set the outcomes of those successes as our goals. For example, if someone becomes the CEO of Google, we say, “you should aim for that. That’s success!”

No, that's ridiculous. Success looks different for everyone. If someone is driven, say, by wanting to save the elephant, then her life’s goal should be to save and nurture elephants. That’s her success.

People have different strengths, and our job as a society and system, which we fail at in schools and colleges, is to help young people understand what they love doing and what they are good at. And if they later realize that their current pursuits don’t motivate them, they should feel free to move on to whatever does.

I myself studied the humanities, followed by the history of science, then became a professor, and then left it to start the Gallery. One may say, I changed my career thrice, and where’s the problem? I’m extremely happy.

To change your mind is not wrong. And to pursue something because you love it, is not wrong. Because when you are driven by something, you will most likely find a way to excel in it.

Let me give you a contrasting example. My husband, who used to teach at IIT Madras, once asked a student why he opted for electrical engineering. And the kid said, “well, my JEE rank.” It’s a tragedy, because there is no room to ask, what did you really want to study? Did you even want to be an engineer?

I think we kill parts of ourselves by selecting professions that do not motivate us, just because they form the current definition of success.

There’s a lovely thing I read the other day: if the path before you appears clear, it means many have traveled on it before. My advice is to find your own path. By all means, admire successful individuals, but don’t try to become them. You have to become the person only you can be.

9. Finally, how do you overcome the fear that comes with choosing an unconventional career path?

If the motivation to do something is greater than the fear that holds you back, that’s how you perhaps know that you should do it.

Some of us are held back because we feel we’ll lose time, or we’ll lose face, or we’ll be blamed for taking the wrong decision. I haven’t worried about that, because in a fundamental way, I have realised that you only live once. What’s the point of paying attention to what some might perceive as sunken costs or wrong decisions? Are you actually going to give up your life and time for something you’re not passionate about?

I first moved to the history of science because what I was doing wasn’t working for me. To start this Gallery, however, I left behind something that was working well for me. But this was just so much more exciting! It isn’t every day that I would get the chance to build a new institution from scratch, an institution that I believed India needed. My enthusiasm for this was stronger than my desire to hold on to something comfortable. It was a risk, and it has paid off.

I’m glad I left behind fear. Life’s too short for fear.